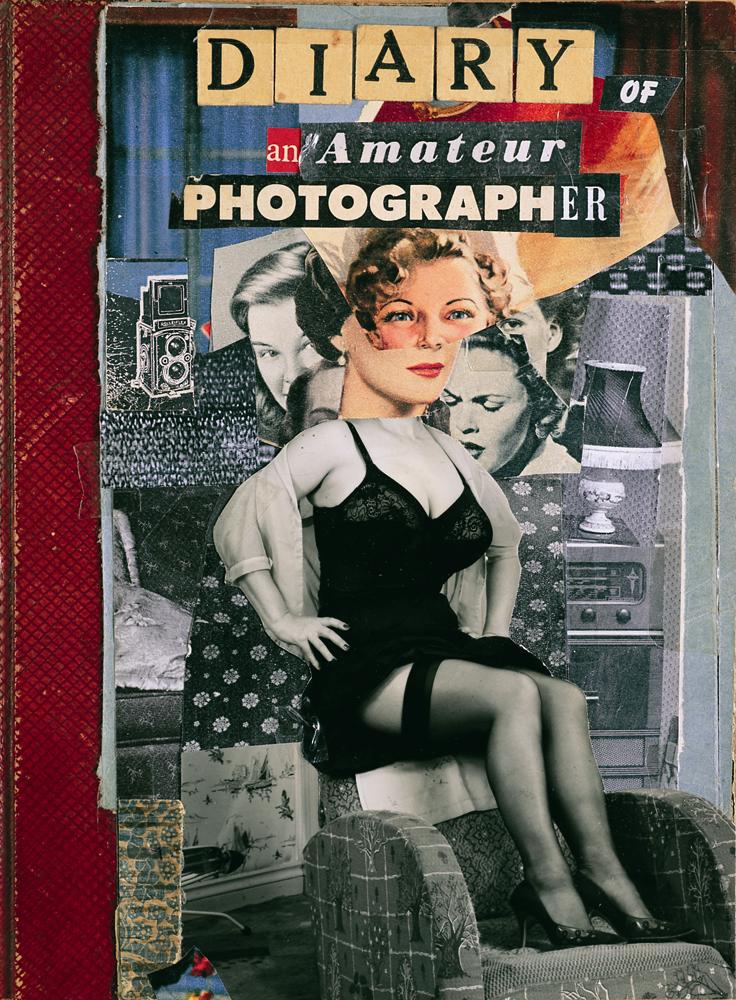

I recently picked up a copy of the book Diary of an Amateur Photographer (1998) by Graham Rawle. A fun and somewhat eccentric whodunnit about an aspiring glamour photographer. It’s a visual treat as the author is known for his use of montage. The book is presented as the protagonist’s diary-cum-scrapbook. There is a terrific and innovative interplay between text and image, which appeals to my design sensibilities. I was going to review the book, but then I thought it might be nice to hear what Graham has to say about it. Below is the text of a presentation Graham gave at a small conference, which he has graciously allowed me to republish. Even though the book is out of print, copies do occasionally appear online for sale.

Photographic ‘artistry’ in 1950s men’s magazines.

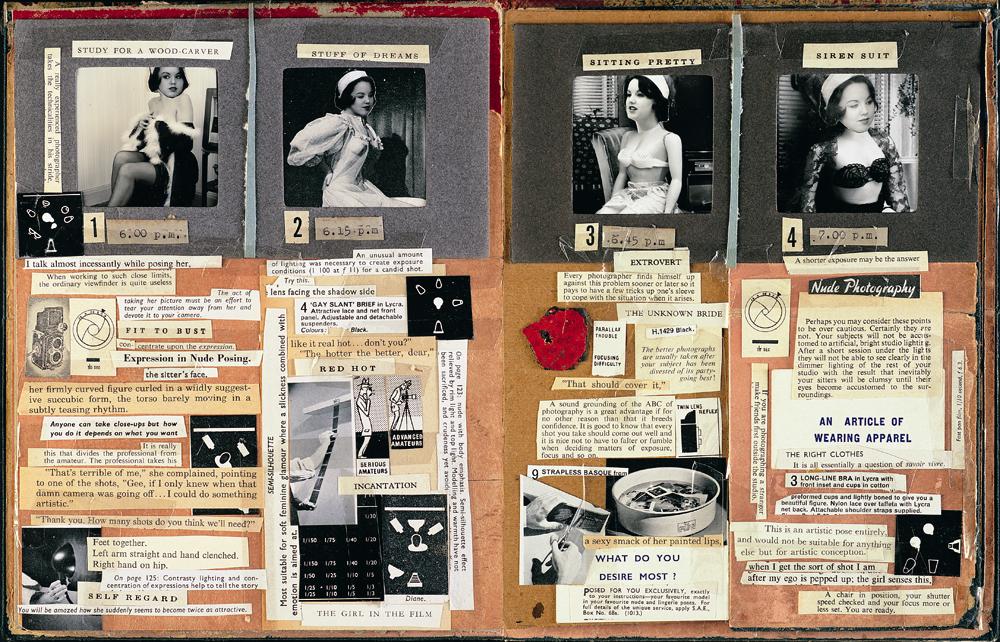

In 1998 I wrote Diary of an Amateur Photographer. Its protagonist, Michael Whittingham, an aspiring amateur photographer, buys an old second-hand camera and finds there is an undeveloped film still inside, with one frame exposed. Curious to know what is on it, he has the film developed and discovers a picture that he believes is a clue to a murder that took place in 1959. He takes it upon himself to investigate further and finds himself immersed in the seedy world of 1950s glamour photography.

Laws on pornography in the 1950s ruled that published material appealing to prurient interest in sex that did not have serious artistic value could be banned as obscene. In an attempt to circumvent these rules, certain men’s magazines began to take their lead from the high art that seemed to elude the ban, dubbing themselves as guides for the amateur art photographer and adopting titles like Line and Form and Studio Studies to suggest artistic integrity rather than salacious titillation.

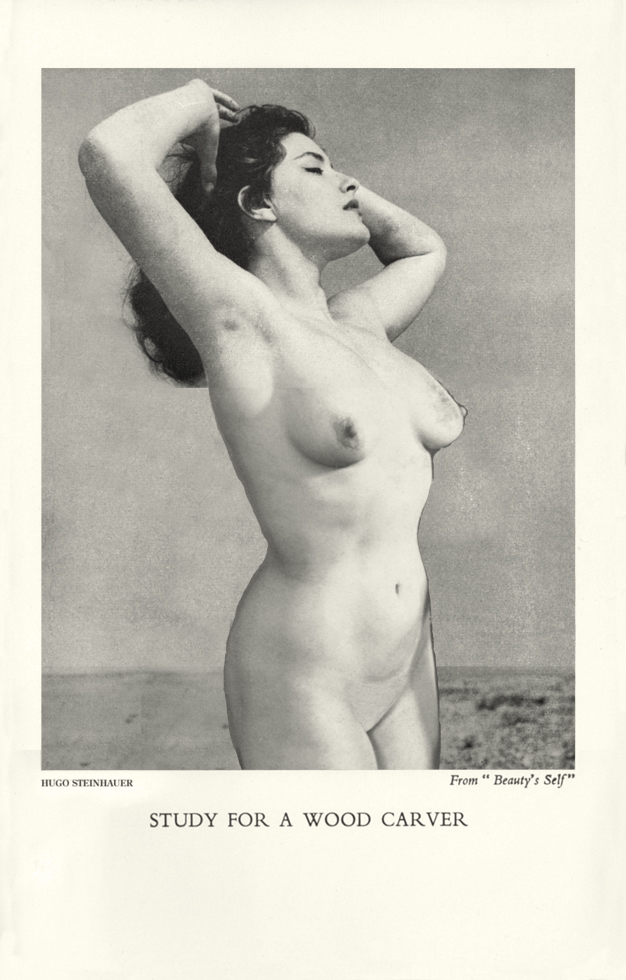

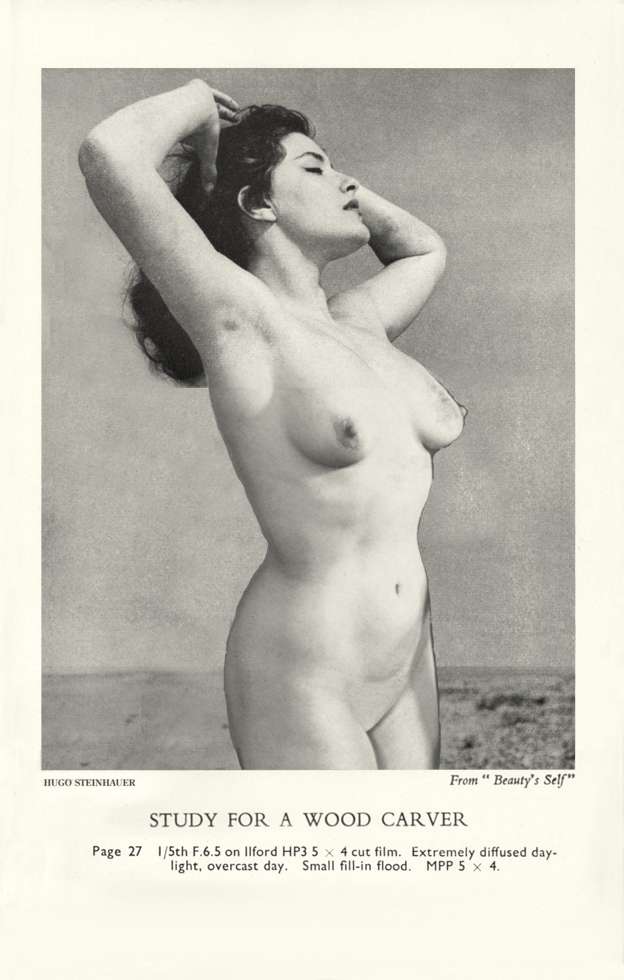

The new publications ‘explored the curves of the female form to demonstrate the artistry of lighting’. Their ‘nude studies’ were now captioned with technical data – f11 at 125th of a second – to substantiate their serious intent. As the loophole in the law stretched, censors were forced to ask, ‘Is it Art?’

My research into 1950s amateur photography extended only as far as its usefulness in informing my central character and the story I wanted to tell. Even then, my interest was not so much in the difference between art and pornography, but in the fascinating grey area that existed between them – a place where my character Michael Whittingham might find self-justification for his questionably furtive thoughts and actions.

As part of his enquiry, Michael decides to step into the shoes of the original perpetrator of the crime and specialise in ‘Artistic Photographic Figure Studies’ – as he prefers to call them.

Reluctant to be associated with anything sleazy or inappropriate, he finds reassurance in any treatise supporting the artistic virtue of nude figure work. Interestingly, the most emphatic arguments defending the aesthetic portrayal of the nude in fine art photography came not from fine art photographers, but from pornographers purporting to be fine art photographers. And, perhaps understandably, Michael can’t quite tell the difference. Yet by adopting their moral standpoint he can exonerate himself from any lascivious thoughts he might be entertaining about photographing the girl from the local cake shop in her underwear.

In the late 1950s men’s magazines like Spick and Carnival that were openly aiming to titillate their readers found themselves constricted by the censors in determining just how titillating they could be. Not very. The most you could hope to see was a glimpse of a stocking top or a woman in her nightie. There was more titillation in the underwear section of the Littlewoods mail order catalogue. Thirsting for more, men were asking where they could get hold of something ‘a little more revealing’.

Without going under the counter to get to the real stuff, there seemed to be two routes open to them. The first was through publications magazines like Health and Efficiency, a monthly magazine celebrating naturism and showing pictures taken at private camps where like-minded people gathered to throw off the constraints of clothing and engage in recreational activities ‘as nature intended.’

These magazines enjoyed more latitude in what they could show because they were about naturism, not sex. Nevertheless, perhaps to attract a wider audience, there was generally a beautiful female model on the front cover. Lured by the cover image, the hapless new customer would get the magazine home only to discover that the pictures inside were mainly of unglamorous housewives peeling potatoes and paunchy middle-aged men smoking pipes and playing badminton. Naturism turned out not to be very titillating either.

The second route was through Art. Nudes had featured in paintings for hundreds of years. How come that was allowed? Well, because it was Art – proper Art – and there were discernible differences between the serious photographic figure studies and the frowned-on cheesecake shots found in magazines like Strip Lingerie and Continental Kuties. For one thing, the models were not wearing, or removing, their underwear; they were not photographed at home in front of the ironing board; and instead of a saucy wink to the camera, they tended to adopt ‘classical’ poses reminiscent of those seen in painting and sculpture.

The latter, it seemed, was generally achieved by simply getting the model to put her arms above her head and telling her to look away from the camera. To reinforce their fine art provenance the pictures were given generous white borders and artistic titles: ‘A Design’, ‘Pulchritude’ or ‘Contours’.

There must have been some formal guidelines by which the censors arrived at their decisions, but much of it must have been down to a judgement call: not so much ‘Is it Art’, but ‘Does it look like art?’

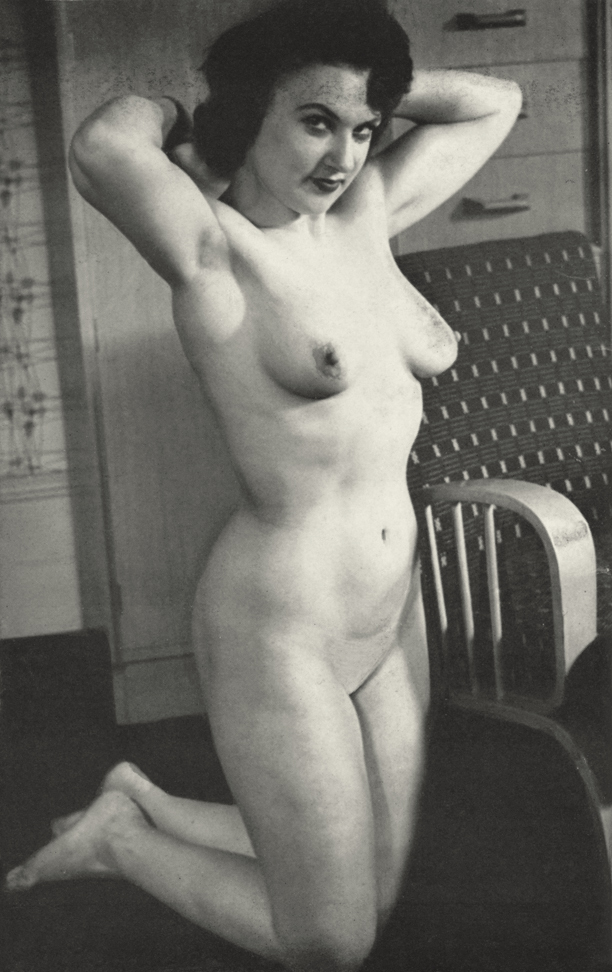

- A model in a tawdry domestic setting. She’s got her hands above her head,

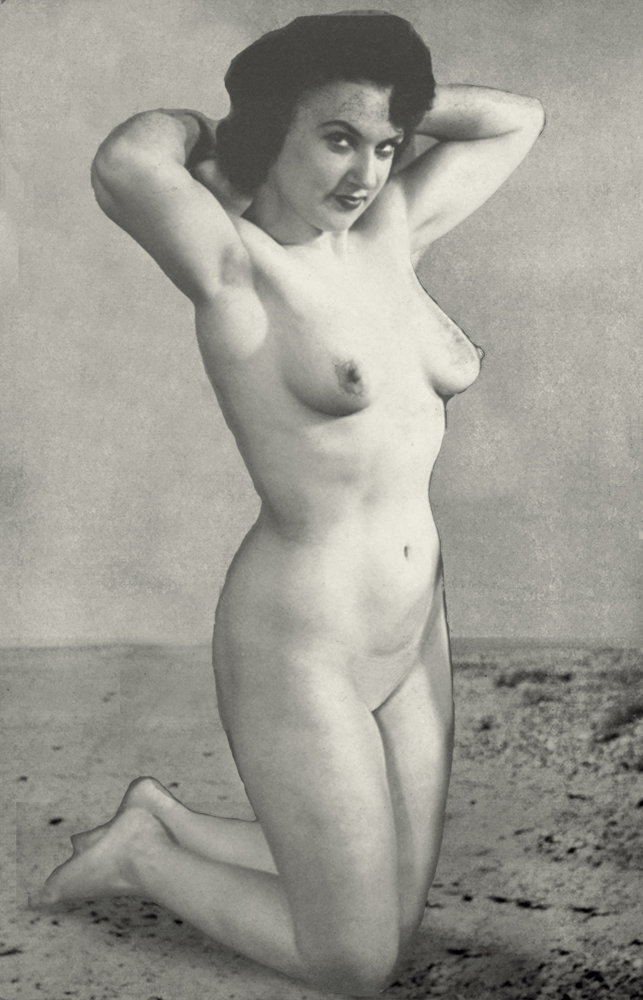

but still it doesn’t look like art (see fig. 1). - Let’s try putting her in an outdoor setting instead. Better,

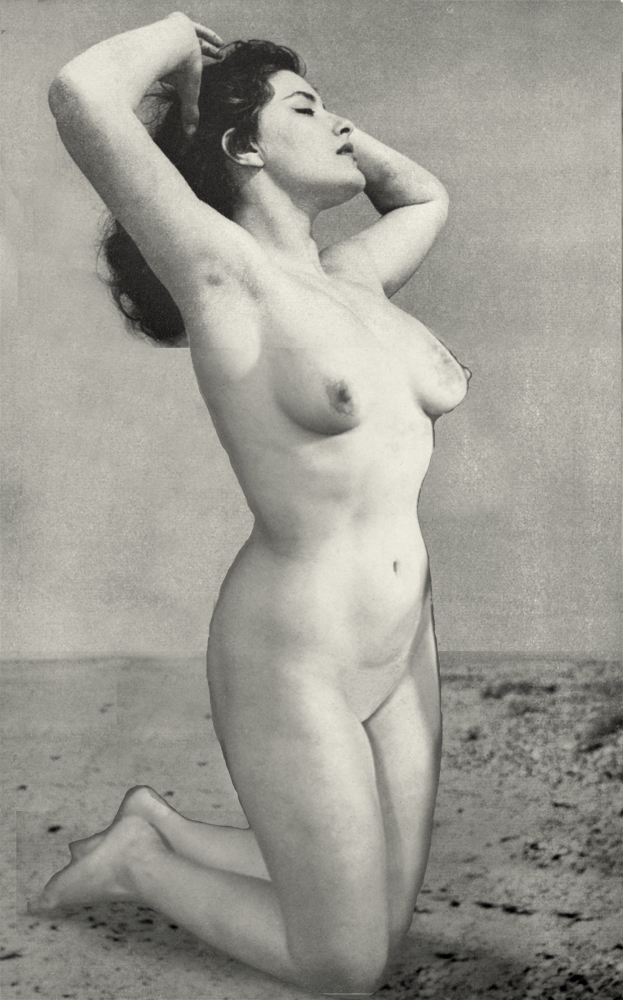

but there’s something licentious about her look to the camera (see fig. 2). - Let’s turn her head away. Nearly there, but we’re missing something (see fig. 3).

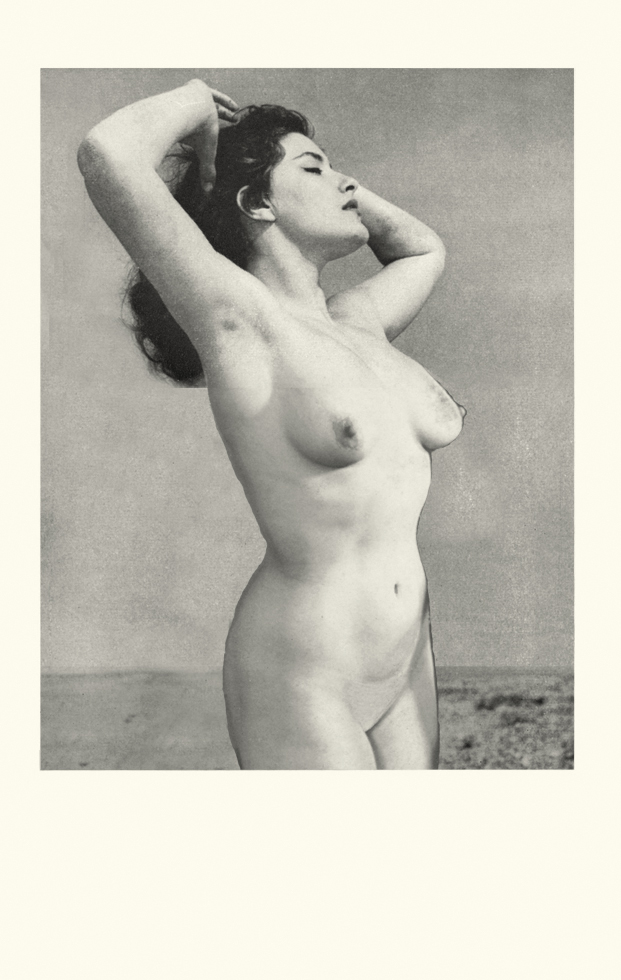

- Of course, it’s the arty white border (see fig. 4).

- And let’s not forget the artistic title (see fig. 5).

- Add some photographic data – it doesn’t matter what it says; no one will read it (see fig. 6).

Hey presto: smut to art in six easy stages.

The magazines worked overtime to bolster their artistic probity.

“Line and Form is published to fill the need of artists and photographers for a varied selection of figure studies to supplement or take place of the live model.”

“Exposure explores the aesthetics of nude photography through the rich unfolding grace and intimate curves of the female figure in light and shadow.”

In spite of their new titles and principled statements of intent, it was sometimes hard to imagine the artistic sensibility of the photographer.

“Right, Mrs Higgins. I see you sitting on the kitchen mat for this pose. The diffused light filtering through the net curtains will enhance your ethereal beauty. I’m going to call this one ‘Seasonal Study No 4: Ice Maiden in Repose’. I think we’ll have the fridge door open for this one…”

Of course, published material was not the only option. There was a third route men could take in their quest for uncensored or ‘unretouched’ material: they could create it themselves.

By the late 50s home developing and printing equipment was becoming increasingly affordable, giving the amateur greater control, and greater privacy. No longer having to worry what the local chemist (who would normally develop the amateur’s photographs) might think of their choice of subject matter, men could shut themselves away in a darkened cupboard under the stairs to print their own ‘artistic interpretations of the female form’.

Many photography manuals of the time dedicated much of their editorial to the subject of nude figure work, offering advice to aspiring amateurs on how they might secure the services of a model and, moreover, how best to expedite the delicate process of getting the model from clothed to unclothed.

Whether you have a professional photographer’s studio or whether you take your pictures in an old garage, always refer to it as your studio. This is extremely important when working with figure models especially since many of the girls you will be working with will be doing this for the first time. It is very important that they feel they are posing for artistic pictures.

A big help is to have some samples of your best figure studies on hand, either in an album or framed on the wall. In this way prospective models can see the sincerity and quality of your work. The photographs you choose for these samples should be especially impersonal and not show the face of the subject enough to identify her. This is to reassure the model prospect that you will not be showing pictures of her in the nude to anyone who happens to come in.

Popular Photography Vol 28, number 6

My character, Michael Whittingham, is quick to adopt this advice and much of his diary is spent preparing his studio (the front bedroom of his mother’s house) in anticipation of an artistic session with the girl from the cake shop.

Lighting set-ups are tested, titles are proposed: ‘Inquietude’, ‘Statuesque’, ‘Nature’s Simplicity’. All suitably artistic and above board. As the proposed session approaches, his diary entries become more erratic, increasingly supplemented by text clipped from the pages of various photography books to allay any doubts he or anyone else might have about the moral rectitude of his intentions.

Michael may seem like a despicable character – his furtive yet prudish approach to sex, his inappropriate objectification of women – but the literature of the day that condones his behaviour plays its part in fuelling this aspect of his persona. It’s easy to see how someone like Michael – unsophisticated, gullible and repressed – could be so heavily influenced by it. It’s true that he seeks it out and tweaks it to suit his needs, but he’s by no means unique in this: the use of a text to defend questionable behaviour has long been common practice in organised religion. And with The Handbook of Amateur Photography by Dr Hugo Steinhauer as your bible, things are bound to turn nasty.

I found this particular area of 1950s amateur photography, with its blurred boundaries between what is considered respectable and what is not, a fascinating area to delve into. But what was most important to me was how I might use it in my story. It provided the perfect vehicle to carry the evidence in the murder mystery narrative and, once brought under scrutiny, became the ideal catalyst to tease out Michael Whittingham’s inner demons and put them to the test.

This essay was commissioned by Annebella Pollen and Juliet Baillie as part of their co-edited online essay series, ‘Reconsidering Amateur Photography’, as part of the EitherAnd photography project funded by the National Media Museum.

To discover more about the writer, artist and designer Graham Rawle, head over to www.grahamrawle.com.

I remember going to the cinema I think in about 1962 and saw a great “B” feature. I would have been 14 back then. This film was a great way of getting around any censor restrictions. In colour and high quality footage. Came under the heading of art. Young women competely nude and full frontal. All were hairy back then of course. They ended up covered in plaster of Paris! To us back then it was amazing. Plenty to think about later! I think it was French.

Yak,

You continue to provide some amazing material in these postings. You should be gratified at seeing more and more books and online sites referring readers to this Pamela Green address. Please keep it up! I’m interested primarily in the naturist/nudist angles of your discussions, but I’m learning (in no small part from these posts) how British glamour photography history is intimately tied to them.

Mark Storey, Washington, USA

Thanks Mark. Kind words